By Leo Stuckardt, MVRDV NEXT

Edited by Rory Stott

This article was originally published in the Spring 2021 issue of Zeppelin Magazine as part of a dossier of MVRDV's work curated by Zeppelin's Ştefan Ghenciulescu and MVRDV's Miruna Dunu.

1. Introduction

Computational Design: A Shift of Objectives

At the end of the 20th century, the opportunities of new design software tools were primarily explored by an architectural avant-garde, who experimented with software in pursuit of new form, structures, and authorships. Today, such tools are used almost ubiquitously in architecture. But far from following in the footsteps of the early avant-garde, in the decades-long push to modernise the architecture profession, the objectives of computational design itself appear to have shifted.

The relation between us as spatial practitioners and our tools is reciprocal. We make the tool and the tool in turn makes us. But what happens when we no longer make our tools? The development and maintenance of sophisticated design software requires vast amounts of resources, and the industry has therefore come to be led by a small number of industry giants such as Autodesk, Adobe, and more recently, Alphabet’s subsidiary Sidewalk Labs. These large companies benefit from economies of scale and market their product to the widest possible audience.

The strategy most commonly employed to reach this broad audience has been to push computational design from its initial aspirations of speculating on formal languages towards increasing ‘pragmatism’. Digital tools are now performance- and data-driven, in most practices acting as a set of tools for quantification, which provides instant feedback on how a given design change affects construction cost, leasable space, HVAC requirements, or environmental performances. By doing so, architectural software now drives architects’ design decisions on a daily basis.

The consequences of this process for the output of the architecture profession can hardly be overstated. The biases and limited amount of quantifiable parameters embedded within computational design software clearly impact the formal language of the architecture they produce. The cumulative effect of so much of the profession using such a narrow set of identical tools has, in effect, been a standardisation of both design problem and solution, contributing to a globally uniform built environment.

Architects have neither the resources nor the expertise to make their own powerful digital tools to rival the software giants; nor can, or should we turn back the clock to the pre-digital era. What can we then do to develop specific design tools that are as diverse, contextual, and experimental as the architecture we wish to produce?

New EXperimental Technologies

Realising the need for custom computational design tools to foster our idiosyncratic architecture, MVRDV created NEXT, a group of specialists who focus on the development and implementation of technological innovation within our practice. MVRDV NEXT works on both stand-alone research of their own and integrated project development, effectively functioning as consultants for project teams across the company.

With a core team primarily trained as architects and urbanists, the expertise of MVRDV NEXT ranges from data-driven design to computational tool making, virtual simulations and mixed-media forms of storytelling. Following in the footsteps of early, visionary proposals like Metacity/Datatown and the House-, Village-, or Regionmaker, MVRDV NEXT is fascinated by speculations on a future that is diverse, participative, data-driven, and equitable. The combination of dynamic workflows and the continuous development of custom tools throughout the design process allows designers to break free from the standardised solutions encouraged by industry software and makes MVRDV NEXT instrumental to MVRDV’s radical design solutions.

2. Case Studies

Immediacy of the Computational Tool

We see the software tool not merely as a means to an immediate end but rather as an evolving design object in itself.

The following case studies showcase three methods of custom tool development, each with distinct objectives and varying levels of immediacy (the time difference between conceptualisation and application of a tool).

In one, a hyper-specific set of scripts processes and exchanges data between two primary CAD and BIM applications used within architecture. Both applications act as platforms allowing for the creation of a digital design tool that is so specific to the task that it could hardly be transferred to any other project.

This is #ToolAsExtension.

In the second, a workflow that collects and interprets geospatial imagery on the scale of big data is constructed out of various open-source scripts, computational frameworks, and applications from different professions. The resulting workflow does not solve a clear problem with commercial value, but rather explores new ways for a designer to understand the context of a project.

This is #ToolAsHack.

Finally, a design for a software interface, animated but not yet operational, proposes a vision for a long-lasting urban development as a dynamic, inclusive game instead of an inflexible, top-down masterplan at risk of expiration.

This is #ToolAsSpeculation.

The Tool as Extension

#economy #efficiency #software-as-platform #project-specific-solution

.png) MVRDV’s custom workflow between Revit/Dynamo and Rhino/Grasshopper was developed for the optimization of a “wild pattern” for the facade cladding of a mixed-use development in Amsterdam

MVRDV’s custom workflow between Revit/Dynamo and Rhino/Grasshopper was developed for the optimization of a “wild pattern” for the facade cladding of a mixed-use development in Amsterdam

Valley is a mixed-use building currently under construction in Amsterdam’s Zuidas. The building includes abundant greenery, and features a public route over the top of its lowest levels in between three towers. To emphasise the sensation of being in a verdant valley, the towers have jagged floors with cantilevers and setbacks creating a rocky landscape. Natural stone cladding, laid in a seemingly random “wild bond” pattern, emphasises the irregular geometry of the massing. Due to the complexity of Valley’s forms and the sheer size of the project (the façade uses over 40,000 tiles covering 42,000 square metres), manually designing this random pattern was simply not feasible. Instead, a computational workflow was developed and executed over the course of 9 months.

- Predominant design software Revit and Rhinoceros, both industry standards for BIM and CAD. Generic, as they serve a wide user-group.

- Both allow for functional modification through custom scripts in Dynamo and Grasshopper respectively. The software acts as a platform for custom tools.

- Technical and aesthetic requirements such as maximum tile length and avoidance of repetition are implemented in the algorithm.

- In a simple interface of buttons and sliders the designer can cycle through virtually infinite configurations of tiles, choose a pattern and make manual adjustments.

- The script provides the designer with visual and technical feedback (tile distributions) and transfer of data between design and bim software is automated.

These custom scripts transformed generic design software into a specific tool to design facades for this one building; they formed an extension to the industry-standard tools that enabled ambitious design choices made independently of any software.

The Tool as Hack

#exploration #analysis #evidence #open-source #cross-disciplinary-tooling #ground-truth

.png) A Neural Network maps graffiti back onto the city of Marseille

A Neural Network maps graffiti back onto the city of Marseille

Taking the form of a large collection of site interviews, photographs, speculative projects, and maps, MVRDV’s research project “Le Grand Puzzle” formed the foundational base for the 13th iteration of Manifesta, a travelling art biennale that in 2020 was hosted in Marseille. The research extensively mapped the city, from socio-economical to environmental parameters. MVRDV NEXT assembled a vision machine.

- Data from Open Street Maps, a crowd-sourced mapping service, provides a detailed map of the road network of Marseille.

- Using an initial open-source script a data-set of 400,000 photographs of street elevations is collected in an interval of 20 metres along all roads.

- A Neural Network based on a second open-source framework (the computer vision framework Yolo v3) is trained to detect graffiti and employed on the data-set of street elevations.

- The resulting detections – approximately 10,000 of them – are mapped back onto the city.

- Road network, position of street view elevations and graffiti detections are stored within qGIS, an open-source Geospatial Information System.

The fact that this study provided little immediate commercial value is evidenced by the scarcity of off-the-shelf tools. The employed scripts, software, and frameworks typically find little application in architecture and were sourced from entirely different fields. Despite being hacked together in this way, the tool suggests uses outside of the pragmatic commercial systems that usually define software development. It reveals unexpected ways of seeing the city and connects the city’s planners to its inhabitants through their informal appropriations sprayed all over the surface of the city, and prototypes ways for designers to gain insights into the context of their design from afar (an instant remote site visit).

The Tool as Speculation

#vision #mock-up #paper-software #long-term #projection #serious-gaming

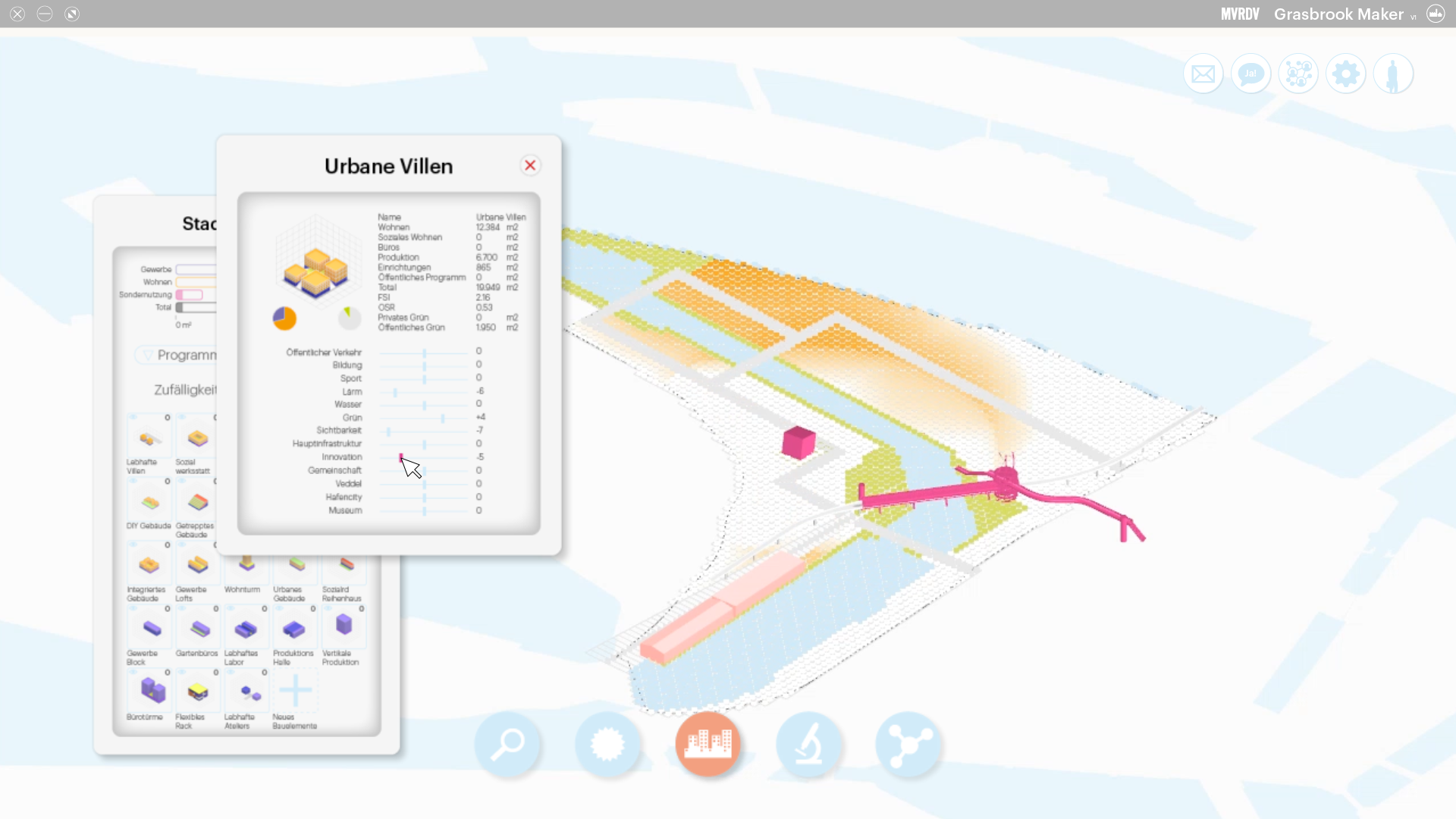

Proposal for a software interface as mediation in a participatory design process for Grasbrook, Hamburg, Germany

Proposal for a software interface as mediation in a participatory design process for Grasbrook, Hamburg, Germany

The Werkstadt Grasbrook, a plan creating 6,000 apartments and 16,000 jobs, is a spiritual successor to Hamburg’s HafenCity plan, Europe’s largest (and among its longest-running) urban regeneration project.

Faced with a similar project, with timescales measured in decades, MVRDV began to consider ways that such a large masterplan could feasibly incorporate the principles of participatory, collaborative urbanism in a way that would cater to the vast number of people affected. Their competition entry proposed a "Serious Simulation Game" called the Grasbrook Maker, a concept and early prototype of a computational tool that aids in the realisation of this vision by enabling constant reassessment and renegotiation between all stakeholders.

- The GrasbrookMaker is conceived as a game to be played by all stakeholders.

- The playing board is defined through the analysis of environmental parameters such as access to water, noise, views

- The designers set the framework, local participants define and place the public projects, developers and entrepreneurs can develop urban blocks.

- Players of this game are asked to collaboratively define their ideal urban layout for the area.

- The Grasbrook Maker completes the masterplan, using an algorithm to automatically place urban elements such as residential blocks or office buildings according to the layout it is given.

- The software takes advantage of simulation to immediately predict the impact of participants’ decisions, and gives players a scorecard with relevant data for their proposal.

- This cycle of input and feedback allows players to iterate their designs and approach the city of their desires.

The Grasbrook Maker shares certain similarities with the most recent generation of industry planning tools such as Autodesk’s Spacemaker and Sidewalk Lab’s Delve. But while the starting point of those tools is to automate existing processes of planning development – suggesting design options to planners based on a list of priorities – the Grasbrook Maker aims to make such processes more accessible and democratic, with stakeholders ultimately using the game to negotiate their own list of priorities. Though the software itself remains in an early prototype phase, the concept acts as a speculation on how the capabilities of cutting-edge machine learning software might serve design goals beyond simply giving form to a financial spreadsheet.

3. Conclusion

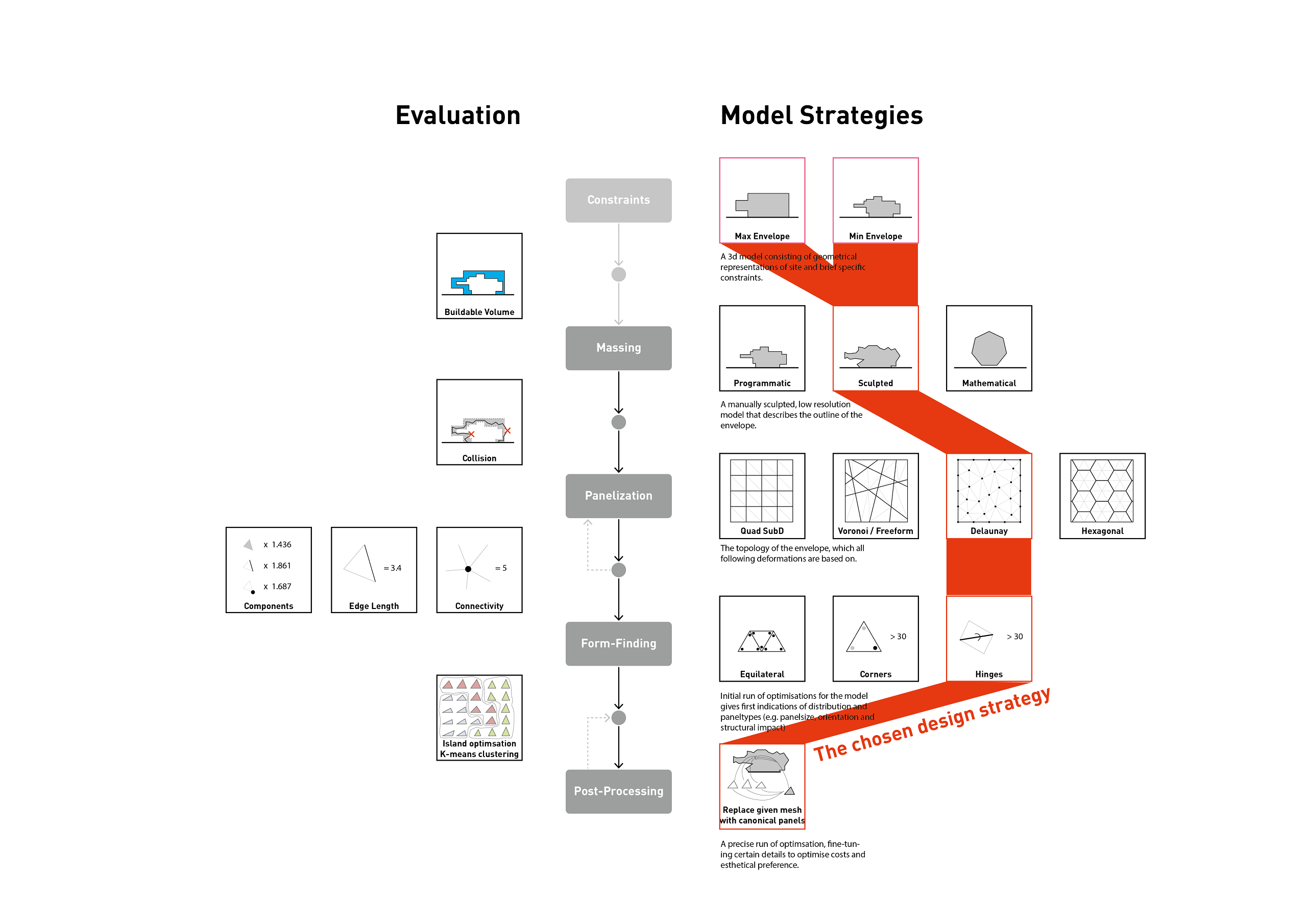

A workflow diagram keeps track of design decisions and corresponding computational scripts

A workflow diagram keeps track of design decisions and corresponding computational scripts

Towards Design Technology as Practice

If we optimise, what do we optimise for? Ideas of optimisation suggest a kind of objectivity, but the design of algorithms and the weighting of parameters is as subjective as any other design choice. (Un)intentional biases and preconceptions might be hidden deep within the code of the design software we use on a daily basis and may, in the long run, affect the shape of the cities we inhabit.

The potential of automation and computational design should primarily expand our design space. The prospects of increased efficiency are important to finance innovation, but we believe that new methods should allow us to arrive at something truly unseen and unimaginable, or to realize something previously thought impossible.

New ways to see and shape our cities require constant innovation of tools and workflows. It is crucial that designers and design firms develop the literacy that is required to play an active role in this rather than waiting for annual updates by Autodesk, Adobe and Esri. Where does this leave the designer? Will urban and architecture design firms transition into IT firms? Or will those very software development corporations that architects subscribe to eventually automate their technology further and go on to replace their former users?

At MVRDV NEXT we want to show that another outcome is possible, and that creating new software is an integral part of the design process. We are excited and optimistic about the fast pace with which digital design tools challenge, enhance, or expand the design space of architecture and urbanism. This is why we make our tools; efficient, raw and diverse.