Stadt Land Schweiz

At first thought, Switzerland seems to be a country free of problems. It projects an image of security and comfort. It does not have waste or pollution problems. Its roads are clean and it has an excellent railway system. It has a beautiful natural environment, lovely cities and picturesque villages. It also has a high level of employment that is the envy of many other countries. So why is a study on the spatial future of Switzerland meaningful?

- Location

- Zurich, Switzerland

- Status

- Competition

- Year

- 2002–2003

- Client

- Avenir Suisse, Zurich, Switzerland

- Programmes

- Master plan

- Themes

- Sustainability, Research, Urbanism

These scenarios are based on the country’s current land use tendencies and the way this can be expected to develop. The illustrated scenarios (project proposals) are designed to help to overcome the complexity of the issues involved by presenting understandable “pictures” and 3D-visualisations. They also aim to avoid the compromises and lethargy that tend to characterize the planning practice in Switzerland. Of course these quasi-realistic visualizations may be seen by some as provocative, but the project proposals should also help to establish focus. They are designed to bring together collective and individual resources in times of uncertainty.

Perhaps they can help to better adapt the country towards a more competitive world. In such projects regions and cantons clearly could collaborate instead of compete. Of course these proposals are embryonic and still require many necessary ingredients. Nevertheless, they aim to inspire the discourse on urban development in Switzerland.

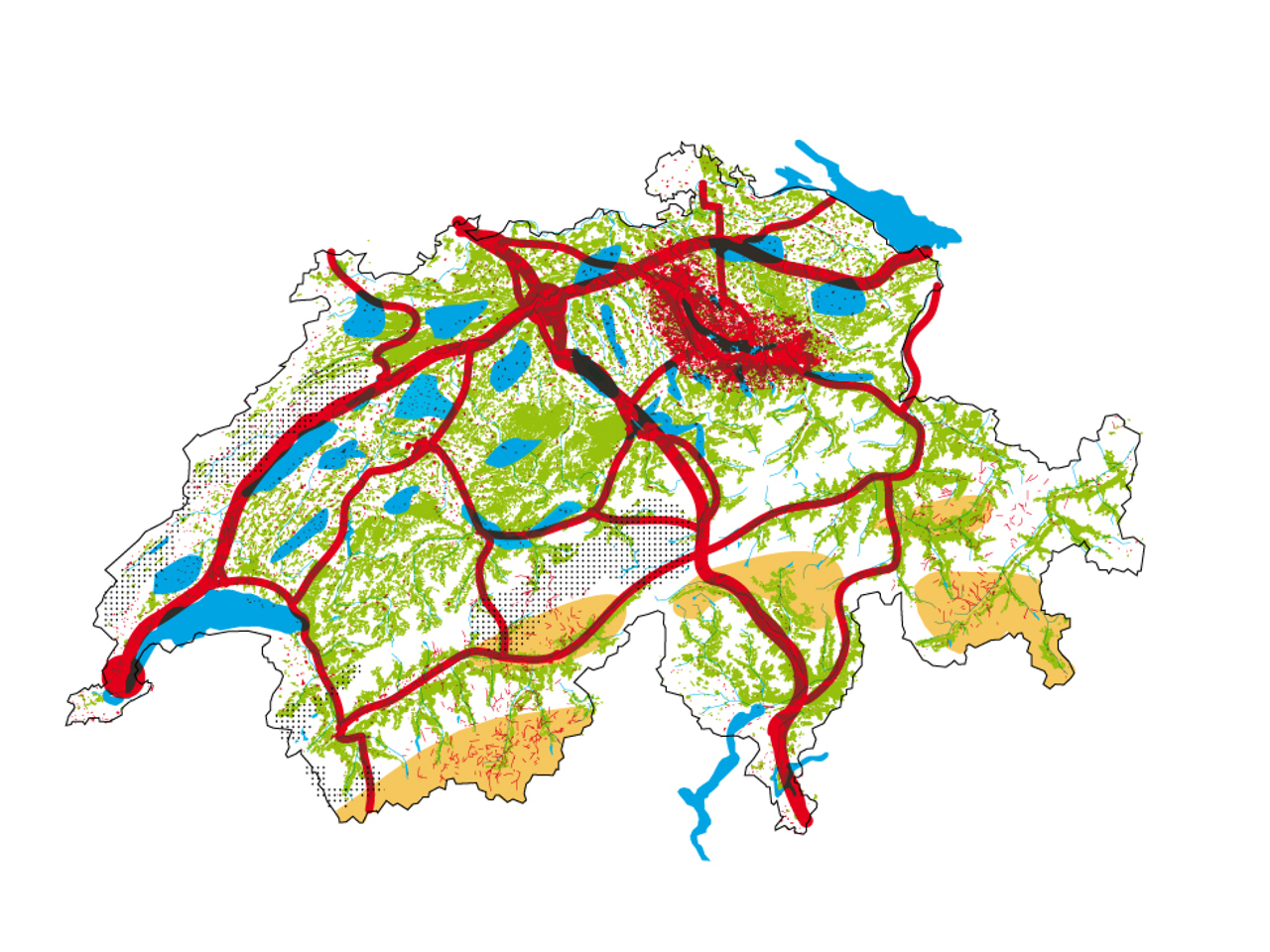

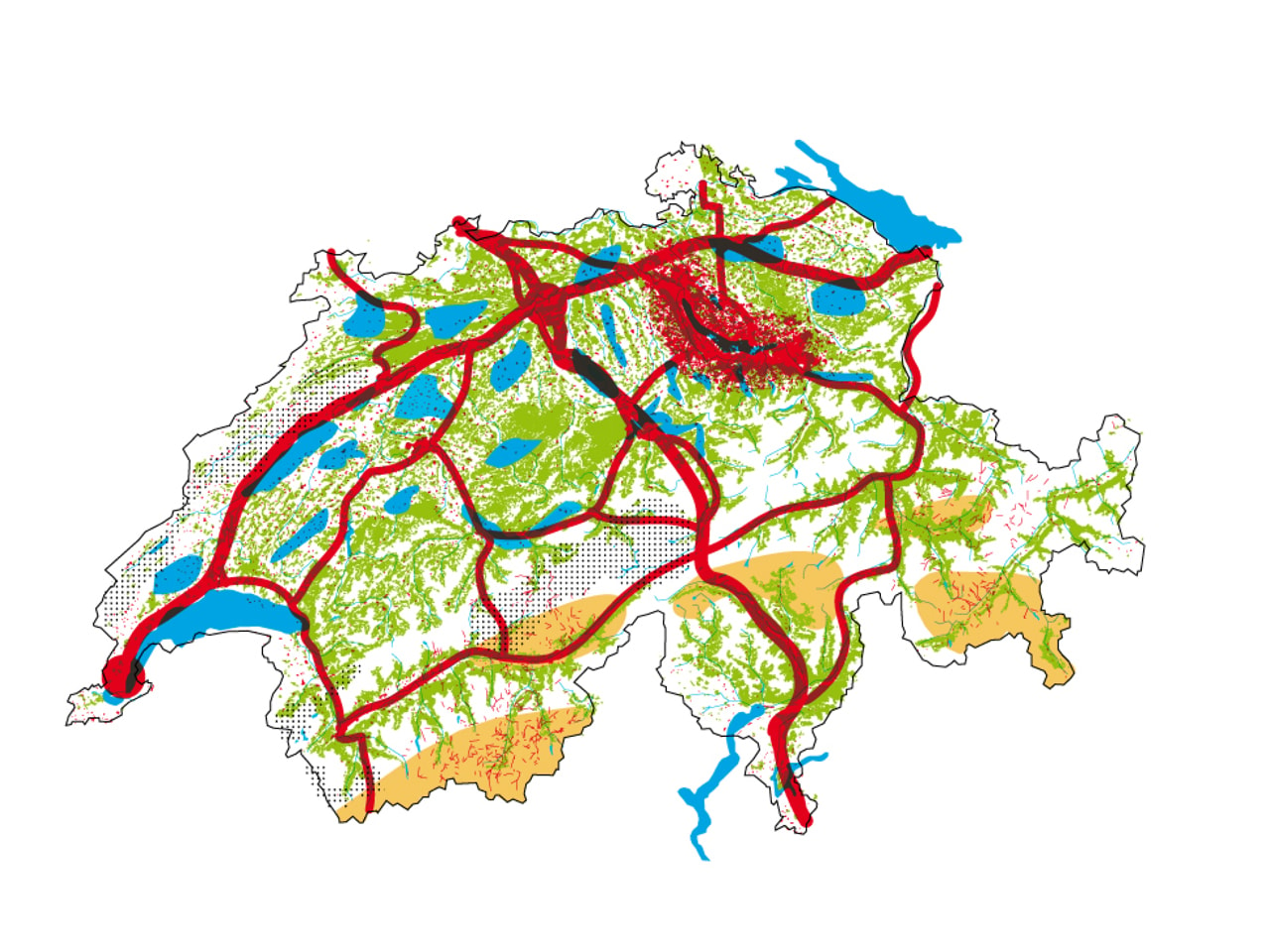

The concept of a “Europe of regions” suggests a number of possible scenarios regarding the role of Switzerland. According to previous density studies the FAR (floor area ratio) within the building zones of Switzerland averages 0.4. This means the utilization rate of the built floor areas within the dedicated building zones in relation to the total building zones amounts to about 40 percent. The degree of future urban sprawl possible will depend on whether Switzerland can encourage greater density in agglomeration areas by conserving agricultural lands as undeveloped areas or even turning them back into forest.

By connecting the current nature zones through new ones, by reducing the effect of urbanization and infrastructure, Switzerland could once again be made into an area for wildlife. One can envisage an almost Canadian atmosphere – no roads and mostly wilderness, bears, eagles and wolves.

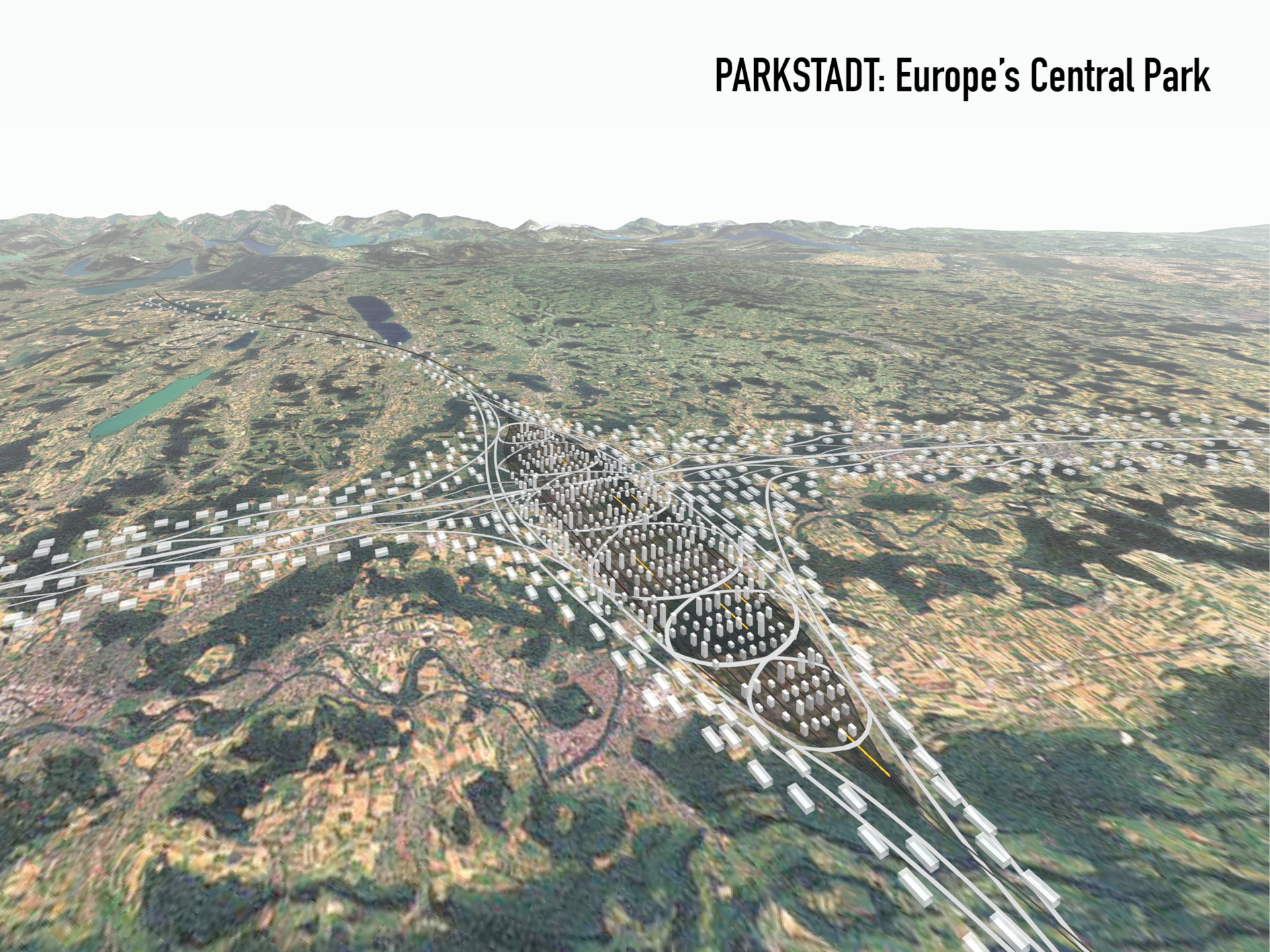

Recent developments show an increased interest in this topic and its potential. Agriculture is losing its former importance; the extension of natural landscape and associated tourism offers an attractive approach to dealing with this. The result could be the transformation of Switzerland into a European Central Park, offering leisure activities and landscapes to rival the French Ecrins or the Canada's Rocky Mountains.

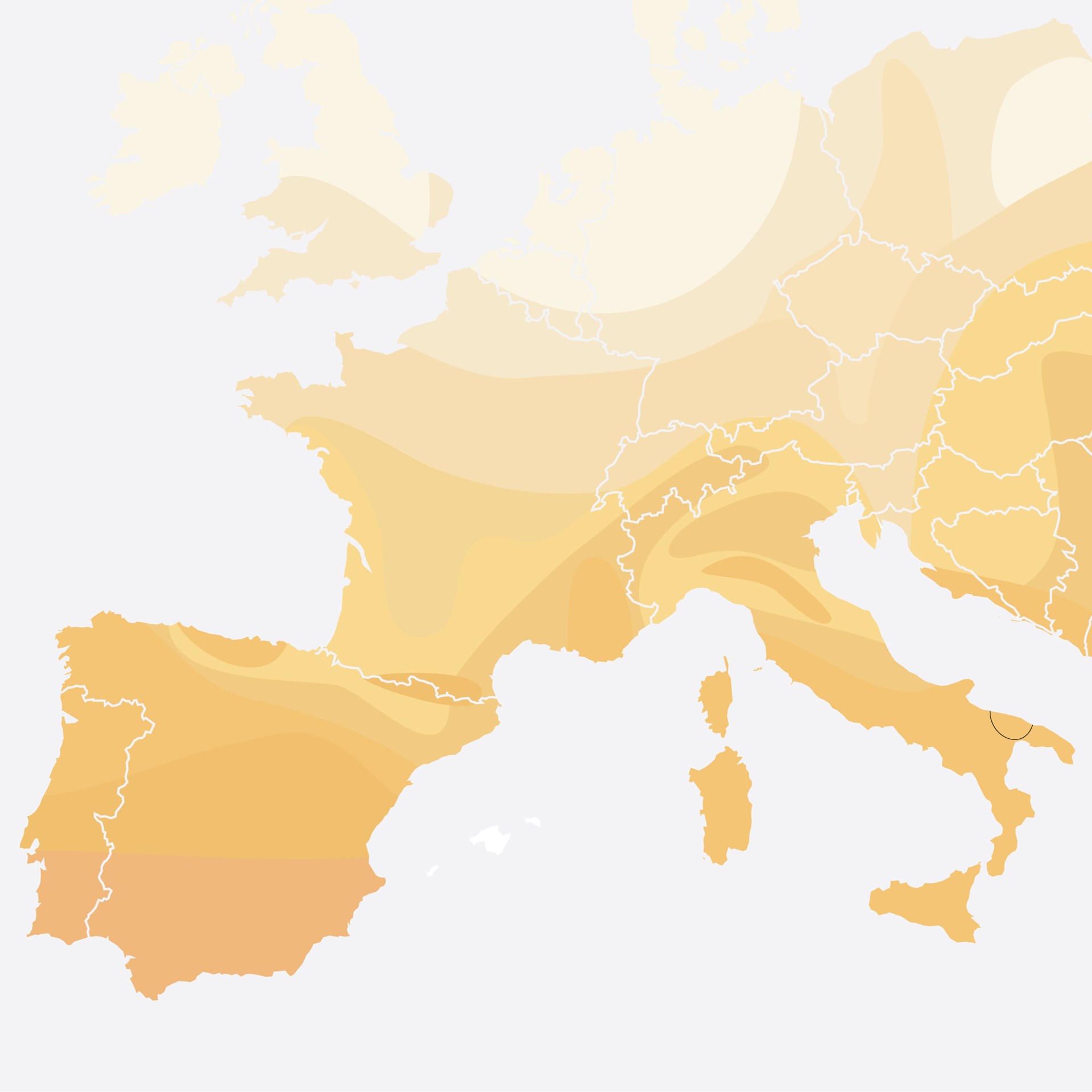

This would not only provide Switzerland with a European role but would also represent a response to some of the requirements of the Kyoto Protocol. It would create oxygen for the rest of Europe and, by providing space for biosphere development; it would help to establish a distinct role for Switzerland as a “Unesco Biosphere”. Connected with zones in France, Italy, Austria and the Czech Republic, these areas of Swiss landscape could contribute to the creation of a southern European park, a counterpart to the natural landscapes of the northern European states.

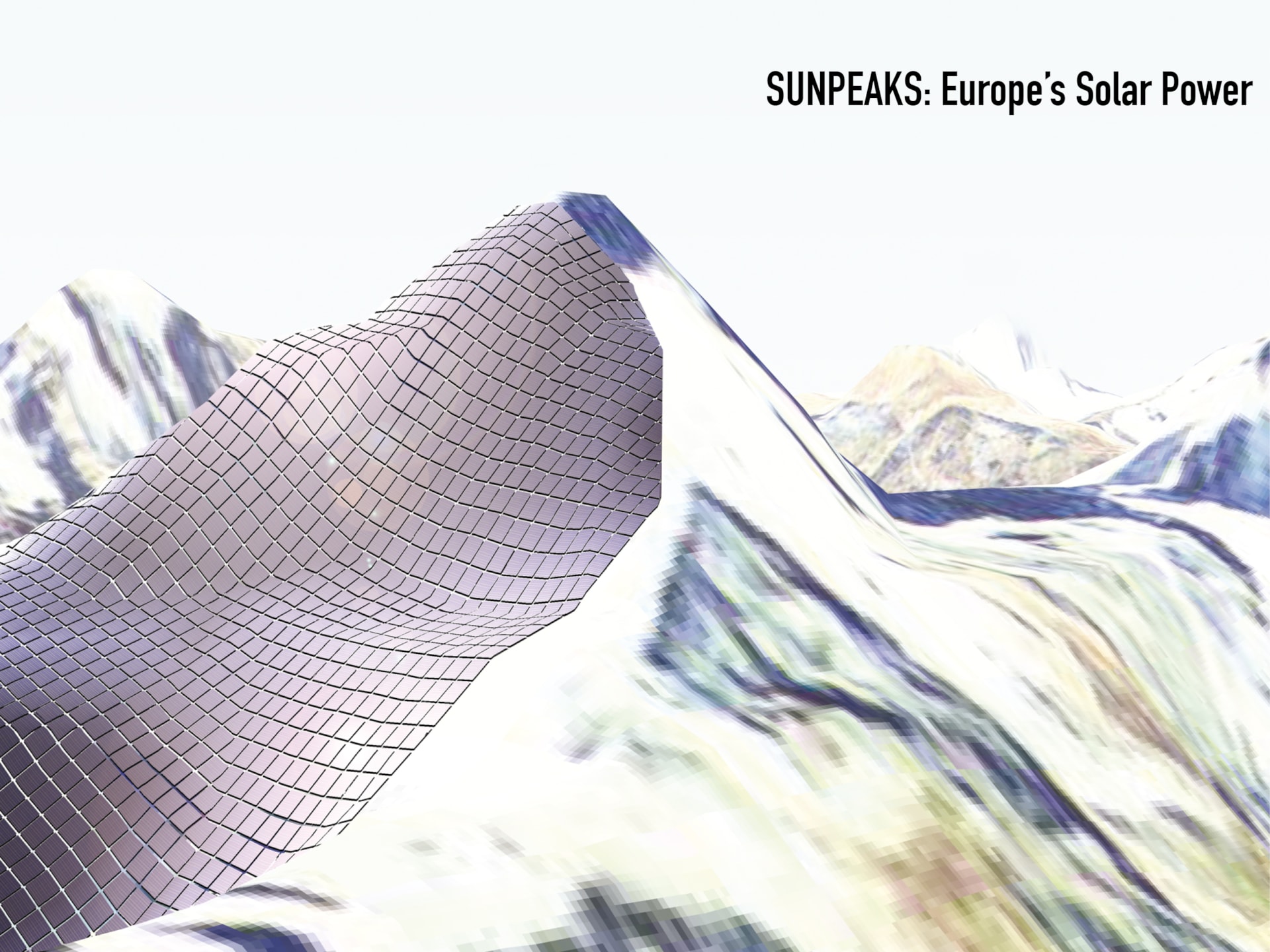

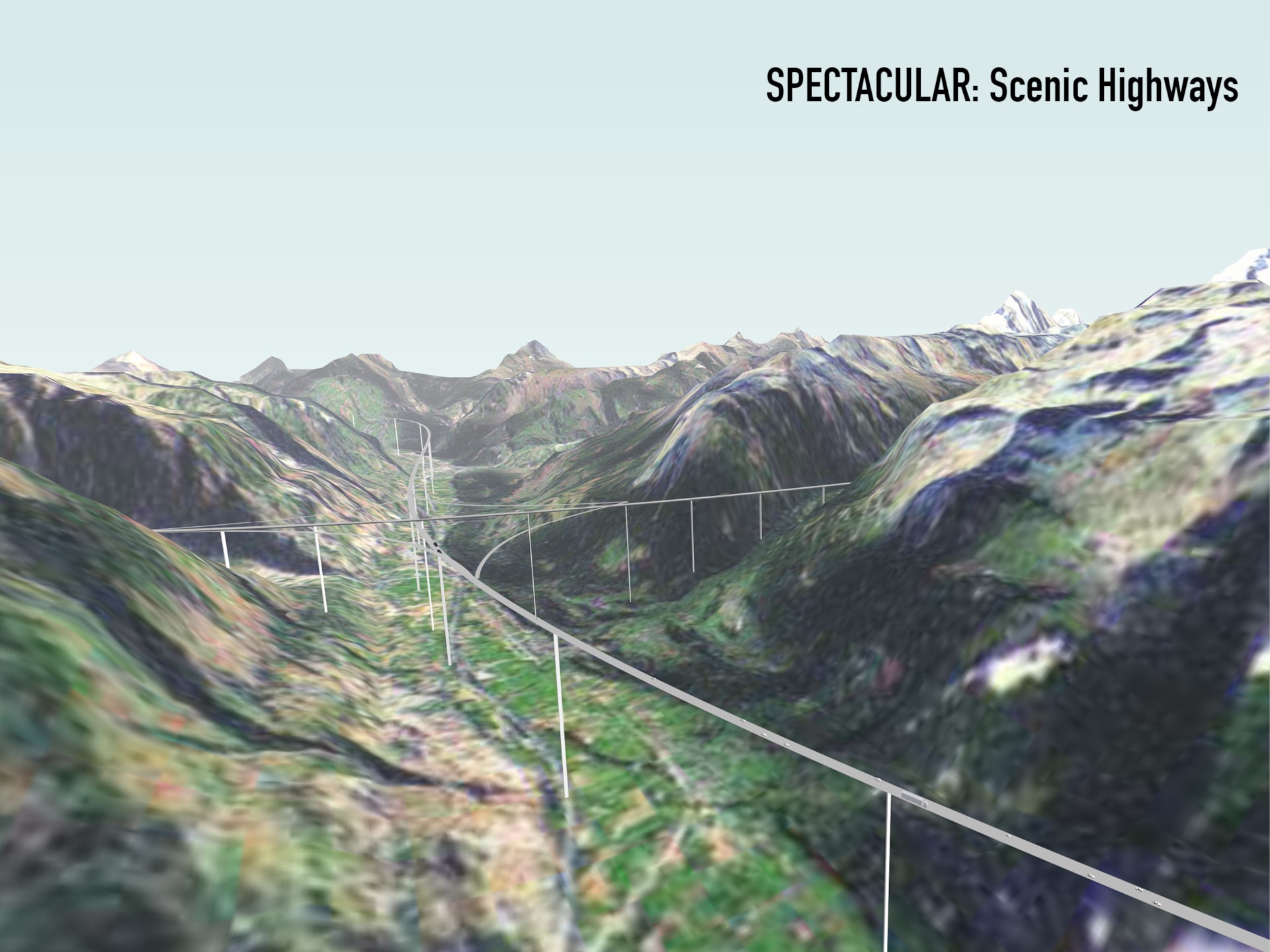

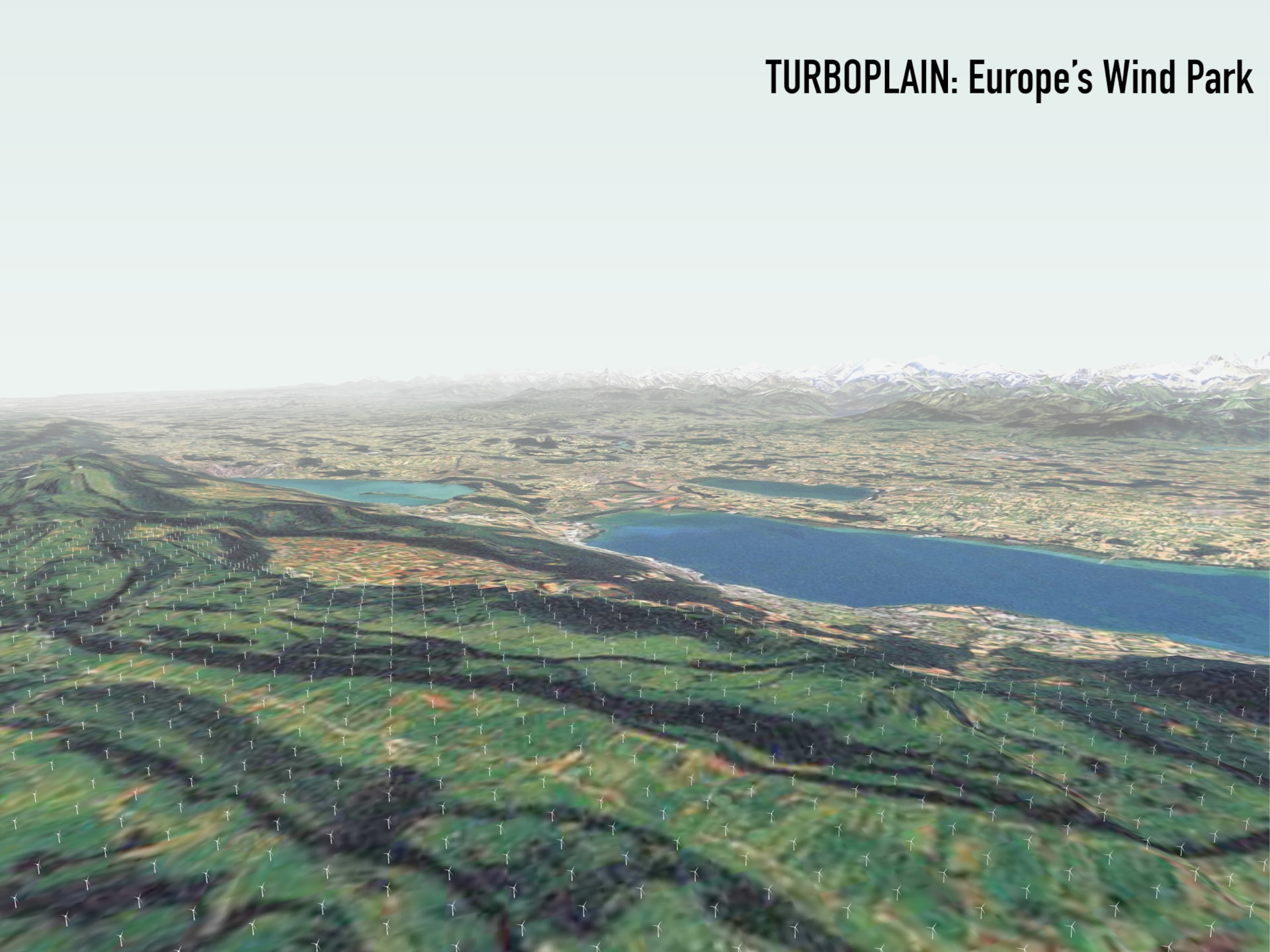

In the park-like areas of Switzerland the road and train crossings should be modeled more like the American park roads and the Canadian train crossings. The high-speed links should be constructed high over the valleys, turning the crossing into a spectacular event, both for the users and for the landscape. The highways should be transformed into scenic highways, with their transit function enlarged by tunnels and bridges. Exits should be minimized, emphasizing the separation of urban development from these areas. In the best wind locations of the Park Switzerland, for instance in the Jura Mountains, a competitive wind energy park can be created. It could generate not only energy for Switzerland but for the rest of Europe as well. If we apply the newest windmills at the proper locations then 34,650 wind turbines would generate 52,000 GWh/year covering 2,166km2 of the land. The wind park can be seen as a landscape protector as well: the density of windmills and associated environmental constraints would protect the landscape from urbanization. In higher regions and locations, solar panels could be easily positioned. The south side of some selected mountains could be clad with solar panels, creating huge solar parks. These installations could supply energy for the whole country and perhaps even Europe.

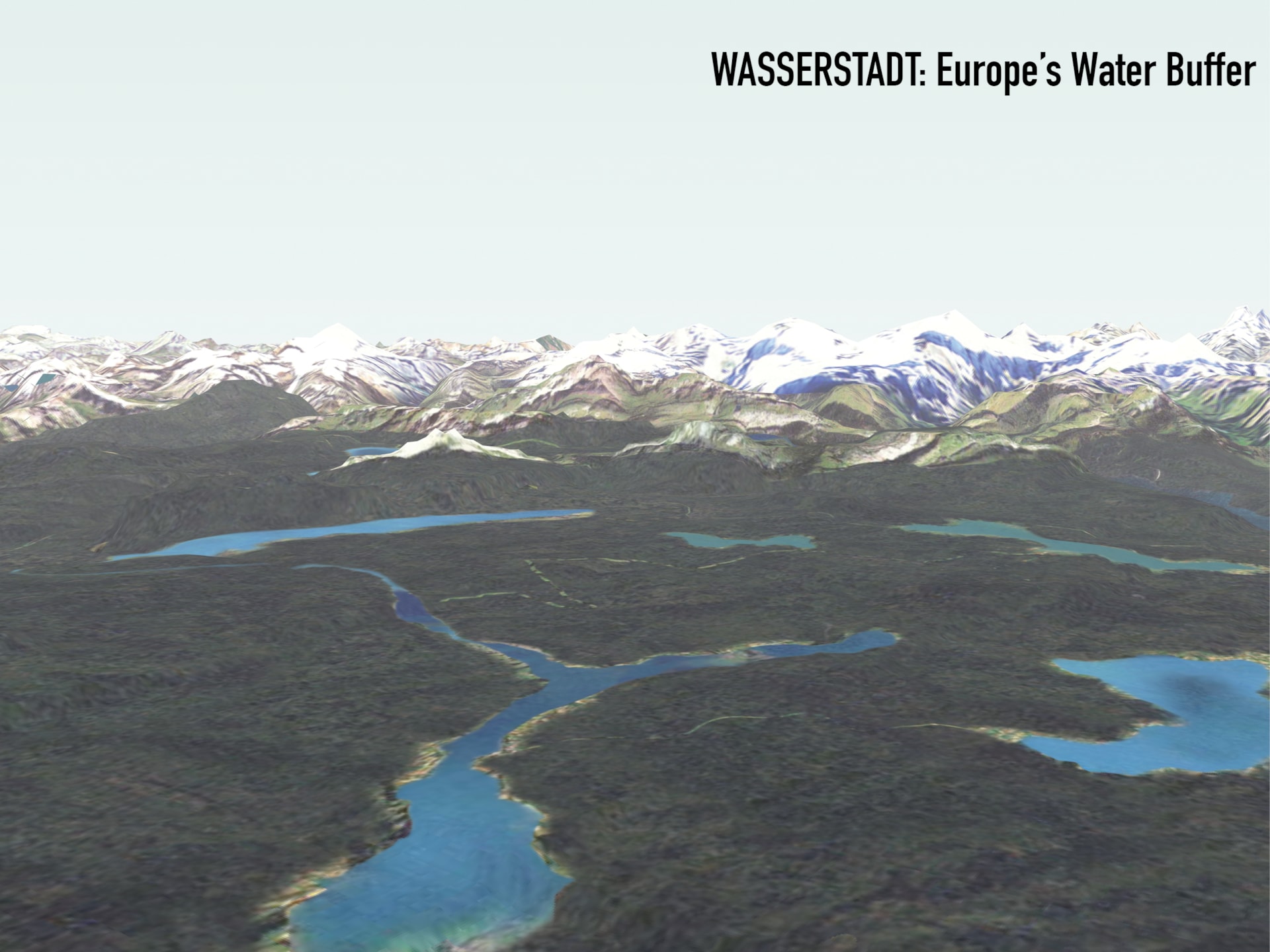

Switzerland also has a relatively high rainfall. It therefore has the potential to serve as a giant water machine for the rest of Europe. This could be created by increasing the buffering qualities of the country. In a selection of valleys, mainly in the Mittelland, a buffering system of rivers, lakes and swamps could be created with the potential to become a European Wetland. It could protect the landscape from urbanization and provide a new function for derelict agricultural areas. Intensive recreation, like skiing, is environmentally damaging. It destroys the landscape, it costs energy, it reduces usage and profitability and it creates ghost towns (in the summer).

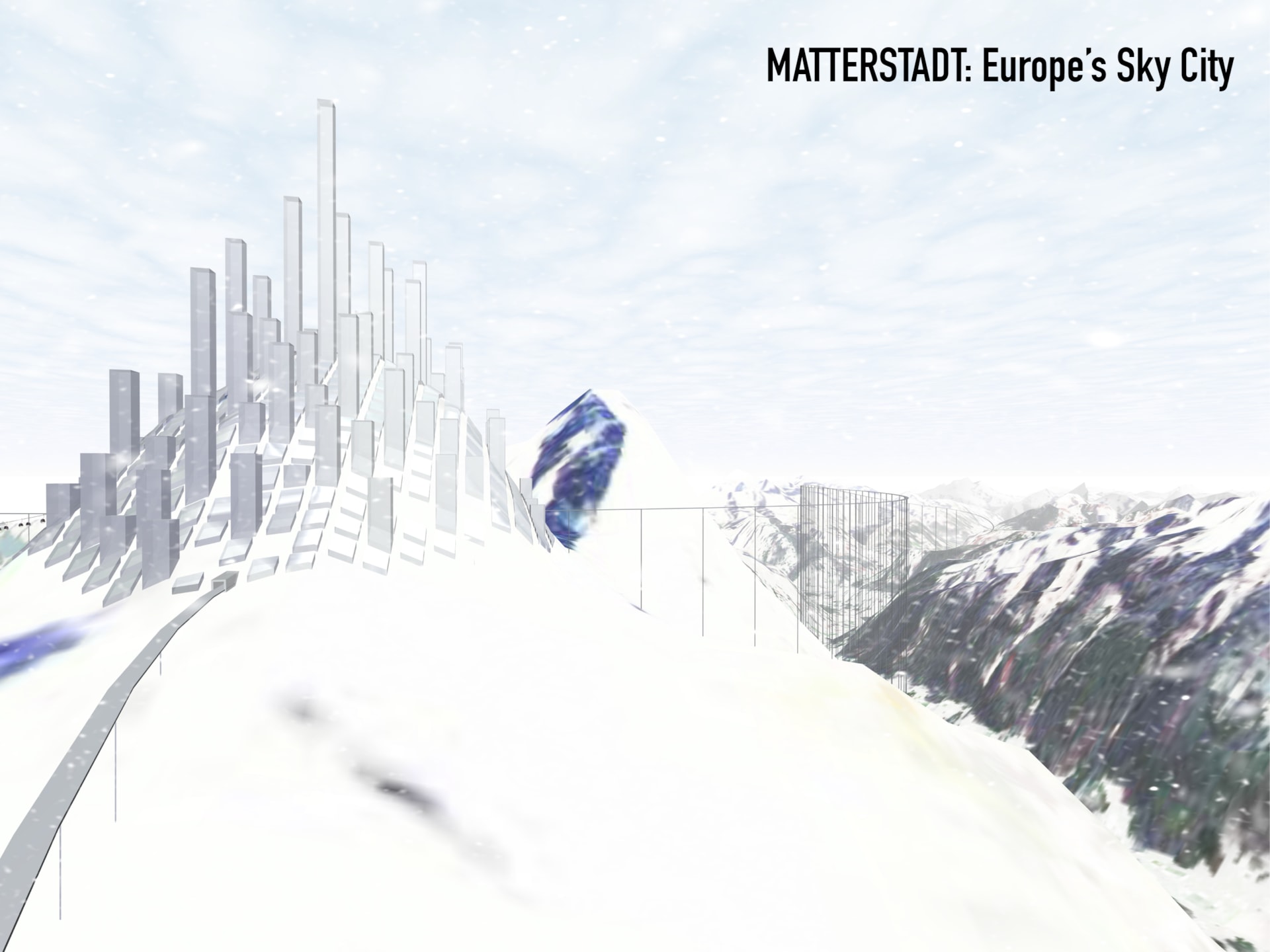

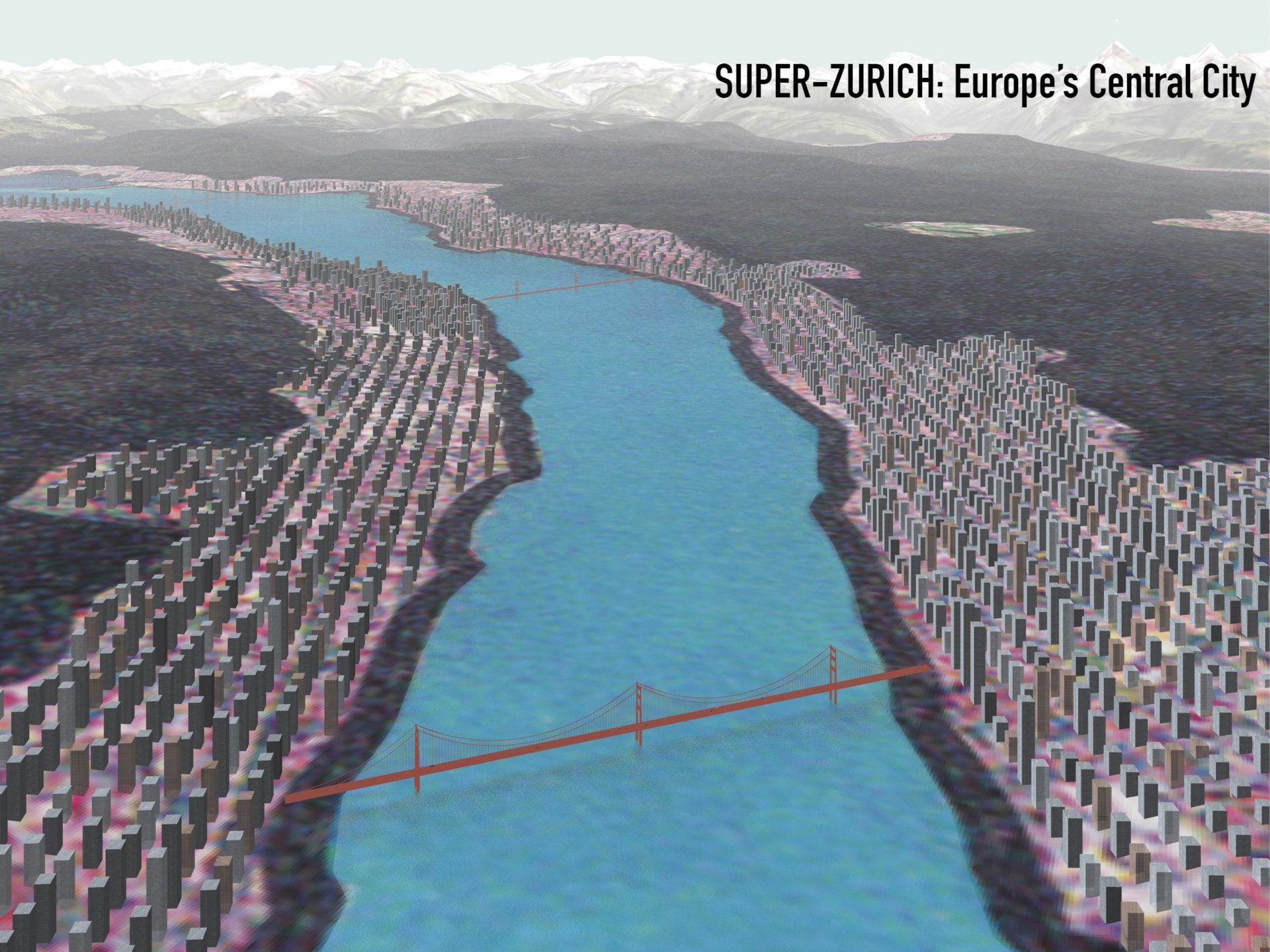

Why not concentrate these zones into one entity, combining the advantages of city life with an extensive remoteness? The result would be a combination of large open wildernesses and a number of concentrated “leisure paradises”: thermal towns and Ski Cities, high up, located above 3000 meters, where there is always snow and ice – the European equivalent of Ladakh. These centers could be connected through the new elevated highways and train links.

Gallery

Credits

- Architect

- Principal in charge

- Design team

- Partners